Fertility planning in South Africa.

For most women, the news that they are expecting a baby is a happy event filled with excitement in anticipation of the arrival of their bundle of joy. However, not all births are “wanted”.

A recent report by Statistics South Africa entitled Unwanted Fertility in South Africa reveals that about 20% of all births in the five years preceding the 2016 Demographic and Health Survey (including pregnancies at the time), happened when women were not planning on having any more children. The term “unwanted” means that no additional birth as recalled at the time of conception was wanted.

Since 1998, South Africa has experienced a decrease in fertility rate with the total fertility rate dropping from 2,9 in 1998 to 2,6 in 2016. Total fertility rate (TFR) is the average number of children a woman would have by the time she reaches 49 years.

The report uses data derived from the South Africa Demographic and Health Survey (SADHS), 2016 and 1998. Women were asked about the planning status of each birth they had in the preceding five years. Typical questions asked in the surveys are: “At the time you became pregnant with [name] did you want to become pregnant then, did you want to wait until later, or did you want no more children at all?”

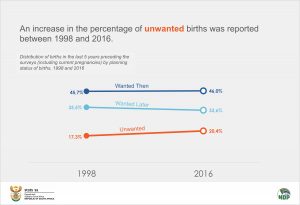

According to the report, there was an increase in the percentage of unwanted births from 17,3% in 1998 to 20,4% in 2016.

Per cent distribution of births in the last 5 years preceding the survey (including current pregnancies) by planning status of births

Older women experienced higher percentages of unwanted births compared to younger women. Approximately 54% of births to women born between 1965 and 1969 were conceived when women were not planning on having any more children; these births were approximately 47% amongst women born between 1970 and 1974. In 1998 and 2016 approximately 12,5% and 14,8% of births to mothers aged younger than 20 were unwanted; this reached a high of 35,3% and 45,5% for births to mothers aged 40–44.

Women with higher levels of education were more likely to have lower percentages of unwanted births. In 2016, unwanted births to mothers with no education almost doubled from 24,8% in 1998 to 46,3% in 2016. Mothers with a tertiary education (11,4%) were four times less likely to have unwanted births compared to mothers with no education (46,3%).

The provincial numbers indicate that the Eastern Cape (26,4%), KwaZulu-Natal (25,1%) and Mpumalanga (25,1%) had the highest percentage of unwanted births in 2016. These provinces, including North West, were the top four provinces that observed high unwanted births in 1998. The increase in unwanted births was more pronounced in the Northern Cape and Western Cape where unwanted births increased from 6,6% to 16,0% and 11,7% to 20,9% from 1998 to 2016, respectively. According to the report, North West is the only province that observed a decrease in unwanted births, from 19,4% in 1998 to 15,7% in 2016.

Accurate measurement of pregnancy intentions is important in understanding fertility-related behaviours, forecasting fertility, estimating the unmet need for contraception, understanding the impact of pregnancy intentions on maternal and child health, designing family planning programmes and evaluating their effectiveness, and creating and evaluating community-based programmes that prevent unintended pregnancy.1

For more information, download the full report here.

1Klerman L.V., The intendedness of pregnancy: a concept in transition, Maternal and Child Health Journal, 2000, 4(3):155-162; Brown, S. & Eisenberg, L., eds., The Best Intentions: Unintended Pregnancy and the Well-Being of Children and Families, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1995; Zabin, L.S. Ambivalent feelings about parenthood may lead to inconsistent contraceptive use—and pregnancy, Family Planning Perspectives, 1999, 31(5):250-251; Bankole, A. & Ezeh, A. Unmet need for couples: an analytic framework and evaluation with DHS data, Population Research and Policy Review, 1999, 18(6):579-605; and Westoff, C.F. & Ryder, N.B. The predictive validity of reproductive intentions, Demography, 1977, 14(4):431-453.