Formal business sector debt in 2016

South African businesses are borrowing more money. The amount of debt held by the formal business sector1 was up 5,9% in 2016 compared with 2015. Total debt amounted to R5,7 trillion in 2016.

The rise in debt was observed in eight of the nine industries, according to Stats SA’s latest Annual financial statistics (AFS) release2. Industries reporting an increase in debt in 2016 compared with 2015 were forestry and fishing (up 19,4%), construction (up 16,9%), transport and communication (up 12,2%), trade (up 11,8%), community, social and personal services (up 11,6%), electricity and water supply (up 11,4%), manufacturing (up 8,9%) and business services (up 1,4%).

The mining industry, however, saw its total debt decline by 10,8%.

Is an increase in debt a good or a bad thing? The answer is, it depends. Businesses borrow money for various reasons. Debt can be used to increase operating capacity to meet future demand, by investing in machinery and equipment, for example. Debt can also be used to meet urgent financial requirements without issuing shares, or to keep a business afloat in difficult times.

Why do companies choose debt knowing how costly it can be? Companies can instead opt to offer additional shares to raise funds. With debt, a company is legally required to pay back the principal amount of a loan as well as any additional interest. There is no requirement to repay money that shareholders have invested. Dividends, which might be paid to shareholders when a profit is made, are issued at the discretion of the business.

Share financing might seem like the cheaper option, but it comes with particular disadvantages that can make it less attractive over the long term. During an economic downturn, shareholders might not want to take on the risk of investing in a business, leaving debt financing as the only option. Share financing can be quite volatile as it depends on shareholder decisions on when to buy and sell shares.

When investors buy shares in a business, they effectively become part owners. In some cases they also become involved in a business’s decision making processes. This might seem unattractive to businesses who might not want to dilute ownership.

So debt remains an attractive option for many businesses.

The rand value of debt on its own does not give an indication of whether debt is contributing to business performance. Something more is required, and this comes in the form of accounting ratios. Accounting ratios are widely used to compare two or more variables on a financial statement that have a relationship with one other. When it comes to debt, some of the most commonly used accounting ratios are the debt-to-equity ratio and the quick ratio.

The debt-to-equity ratio provides a measure of how much debt (both current and non-current liabilities) a business or industry has incurred to finance its operations relative to equity. Equity refers to the total value of shares held by all shareholders and profits retained from previous years.

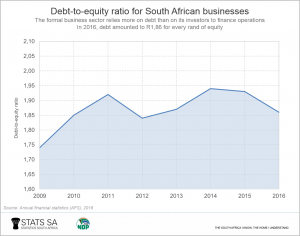

The debt-to-equity ratio is an indication of reliance. It answers the question: how much does a business depend on debt? A ratio higher than 1 indicates that more debt (e.g. bank loans) is being used to finance operations. A ratio lower than 1 indicates more reliance on capital from investors.

Since 2009, South African businesses have relied more on debt than on equity to fund their operations. For every rand of equity used in 2009, businesses utilised R1,74 in the form of debt. This has fluctuated over the years, with the ratio at R1,86 in 2016.

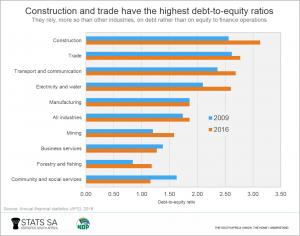

The construction and trade industries had the highest debt-to-equity ratios for both 2009 and 2016. All industries increased their dependence on debt, with the exception of manufacturing, business services, and community and social services.

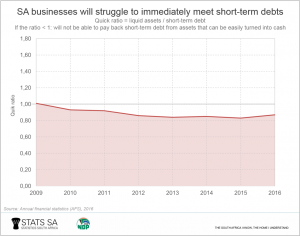

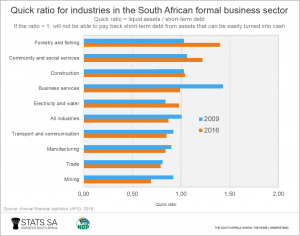

The quick ratio, the second accounting measure explored here, provides an indication of how easily a business can meet its short-term (current) debt obligations using assets that can be quickly turned into cash. If the ratio is above 1, a business is in a position to immediately pay off its short-term debt if it’s forced to do so. The higher the ratio, the better a business’s liquidity position.

The quick ratio for the South African formal business sector was 0,87 in 2016, lower than the ratio of 1,01 recorded in 2009. For every rand of short-term debt in 2016, businesses had 87c in the form of liquid assets. This is not enough to immediately pay back short-term liabilities.

Forestry and fishing, community and social services and construction were the only industries that recorded a quick ratio higher than 1 in 2016, while trade and mining had the lowest. Business services saw a decline in its quick ratio from 1,43 in 2009 to 0,99 in 2016, and mining fell from 0,92 to 0,69.

1 Formal business includes private businesses and public corporations.

2 Download the latest Annual financial statistics (AFS) release here. The AFS survey measures the financial health and performance of each industry, including information on turnover, purchases, and capital expenditure. The report sources data from the financial statements of enterprises (i.e. private businesses and public corporations) in all industries, with the exclusion of agriculture and hunting; government and educational institutions; and financial intermediation, insurance and business services not elsewhere classified.